I haven’t talked with others about these places and statues. My conversations with other pilgrims usually veer in other directions.

In Lucca, I visit the church in Lucca where the body of St. Zita is claimed to be “incorruptible”; in numerous churches, I see statues of headless saints holding their own heads; in Bolsena, I visit the church’s altar where a medieval priest who doubted the doctrine of transubstantiation discovered that the consecrated host actually bled blood while he celebrated the Eucharist.

My reaction to these bodies, statues and altars has been to look at them, usually in a puzzled way. Then, I file them away. Another statue photographed. Another old church visited. Another chapel and altar. As a mainstream Protestant, I acknowledge and move on. These places and statues are simply to foreign.

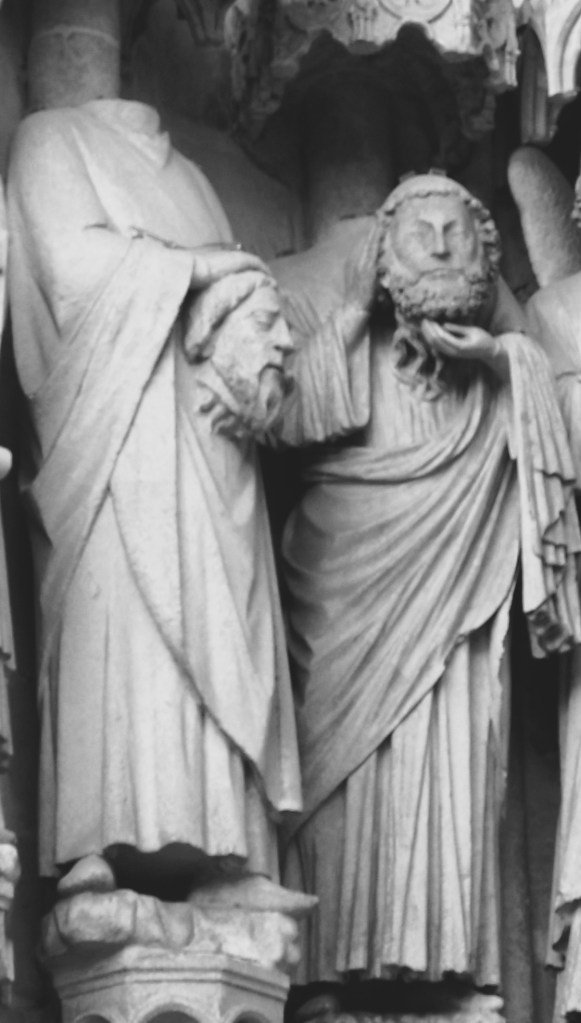

Of course, there is more to these bodies and places than I’ve mentioned. Concerning the “incorruptible” St. Zita, she was born in 1218 and died in 1272. Apparently, she was a poor, but devout young girl of Lucca who for decades simply did her servant work. After her death, her body did not decompose. In 1580, the church put her body on display; in 1696, the church canonized her as a saint. She is one of the “Incorruptibles”, like Saint Rosa in Viterbo, who are among the 100+ saints classified as such. Footnote: the Roman Catholic Church does not require all saints to be an “Incorruptible.” Regarding the statues of behead saints, one o the most famous is St. Denis of Paris. While the Roman Catholic tradition often claims that these individuals moved and spoke after their death, the statues themselves tell a more simple story. This person was martyred for their faith. The church claims over 120 individuals who fit the category of “cephalophore”, “head-carrier.”

As I briefly think about these places and statues, I can ask all sorts of legitimate questions. Laying aside all questions about their “truthfulness” and what that expression means, I’m struck by five assumptions and implications from these claims. Let me explain.

To begin, the Roman Catholic Church asserts that these occurrences don’t occur naturally. Instead, these occurrences are evidence for a belief in the supernatural, in God’s engagement with this world. Similar to Aquinas’ five poofs for the existence of God in the intellectual world, these are “proofs” of God’s engagement in the world of popular religion. “Proofs” for us common folk. Second, the Church becomes involved in these occurrences by conferring recognition and status to the event or person, canonization as a saint or creation of a festival such as the Festival of Corpus Christi. Not only do these occurrences catch the “eye” of the church, but also the church now catches the “eyes” of its faithful concerning these special events. A third implication is that for the church these occurrences are not isolated occurrences, rather they form a varied, diverse, and consistent way in which this God interacts with the world. From these occurrences follow a fourth implication. For the Roman Catholic Church, there are tangible places which have a gravitas to them; particular “spaces” which seem to be a location where God and the world intersected with greater intensity. Finally, these “spaces” are not only known, but practical implications follow for the Roman Catholic faithful. Namely, a person can go on pilgrimage to these sites. Since the faithful’s sense of the divine is not as “diluted” as in other settings, the pilgrim can find both the memory of that divine presence, and hopefully, can find a present “concentrated” presence of the divine. Think Fatima and Lourdes. These places are “sacred” and “holy.”

In the classic Protestant tradition of Luther and Calvin, there are no more special places of such weight. While religious and non-religious folk alike, distinguish between spaces, some more valuable, some more important, than others, Roman Catholics can embrace a tradition where the “sacred” and “space” are especially close.

So, all of these bodies, statues, altars, their places, convey a sense of foreignness to me. As I engage in trip after trip of slow-travel, I wonder about the Protestant notion of pilgrimage, such as John Bunyan’s Pilgrim Progress. This classic allegorical Protestant work doesn’t have a sense of sacred place; instead, this work seems to float above a sense of particular place, a special space. What does this mean for classic Protestants today? If contemporary Protestants are hoping to reclaim a religiously significant sense of pilgrimage, as distinct from other acceptable forms of slow-walking, should it explore more this notion of “sacred space.” I wonder….