There is no other good way to visit the three villages associated with William Henry Kingsbury. So, I cough up 120 pounds for three hours. Although Vince, our driver, doesn’t know much about Winterbourne Whitechurch, Milton Abbas or Morden, he is a safe and pleasant driver.

I’m not entirely sure what to expect. I’ve walked through twenty or more villages. They all vary. I’ve seen Turner’s and Constable’s 19th century paintings. The paintings often offer an idealized and rural romanticized village life. I know not to expect those types of villages. I do know that villages have changed. Because my maternal grandparents lived in rural Illinois, I can picture tangible reminders of village life 100 years ago. The rusting train tracks. The grain elevator. The Baptist and Methodist churches. The primary school (I think). Our grandfather’s store. Houses which received electricity in the 1930’s. Houses without indoor plumbing. I imagine England was no different.

We stop first at Winterbourne Whitechurch. This village is on the historic toll road from Blandford to Dorchester. In 1753-1754 responsibility for upkeep of the road shifted from the village’s parish to the Harnham, Blandford & Salisbury Trust. The village grew up along this road and the road that leads to the parish church. Driving directly to the parish church, we pass a small post office and a building that has “Reading Room” engraved in stone above the entrance. Before entering the church property, I pass a thatched building with the sign “Church Cottage” in the window. I wonder if this is the thatched cottage in a photograph that my cousins remember.

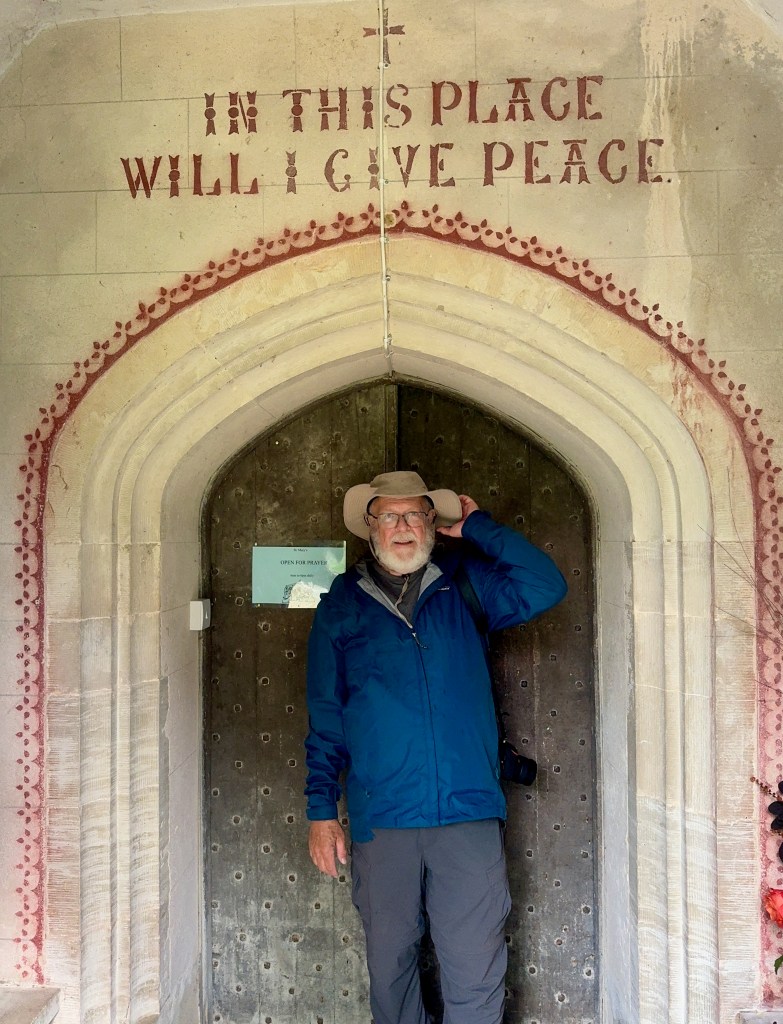

St. Marys is a small, typical parish church. However, unlike most churches that I’ve seen, this church has a painted pulpit. There is also a small, framed information sign stating that one of this church’s rector was the father of Samuel Wesley. Later, Samuel Wesley became the father of John Wesley, the “Father of Methodism.”

A cemetery wraps around the church. Although we know the burial section and plot numbers of William Henry Kingsbury’s grave, I know that we won’t find any tombstones. How could the surviving family members of a poor agricultural worker afford a tombstone? I do enjoy simply strolling through the cemetery. When I see a tombstone from the later 1800’s, I imagine the intertwining lives of that person and my great, great grandfather.

We travel next to Milton Abbas. Before stopping in the village, we proceed to the abbey. Unlike Winterbourne Whitechurch, Milton Abbas is described as “Dorset’s village jewel.” As early as 934 CE, an Abbey Church was built by the Saxon King Athelstan, grandson of Alfred the Great. The Abbey commemorates the spot where King Athelstan had a vision that he would defeat the Danes. He did. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539, the abbey fell into others’ hands. Eventually, in the late 1700’s, the landowner decided to destroy the nearby village and make a new model village in a new location. In reality, the older, existing village interfered and marred his view. He wanted a beautiful setting and view from his manor. What the powerful can do!

While in Milton Abbas, we take a side trip to a medieval abbey. Since 1952, the abbey has been a private boarding school for wealthy English kids. Undeterred by “Private Property” signs, we find a reception office. Closed. We find another office. Empty. Upon hearing footsteps, I wait until a young father carrying a toddler enters the hallway. Although surprised that Mary and I are here, he gives us permission to enter the chapel. “Just the chapel. Don’t go into the other buildings.” The chapel is large, and obviously well-funded through the centuries. As part of a monastery, I doubt though that any of my ancestors saw the chapel’s interior.

We return to the main village road. Relying upon the designing and landscaping assistance of Capability Brown, the landowner built thirty-six identical cottages flanking the main road. In the middle was the parish church. Despite the upheaval, I have to admit that the result is beautiful.

Mary and I visit St. James, the parish church after an elderly couple enters. A large banner indicates their reason for entering “Coffee, Tea, and Cakes.” Sounds fun. Joining the group, we are welcomed by the vicar and a dozen others. Since this church was the home church of William Henry Kingsbury’s parents, we ask if anyone has heard of Kingsburys. No luck. But, again, I’m not surprised.

Our final stop, probably ten miles further east, is Morden. Morden was the home of Jane Way, William Henry Kingsbury’s wife. How did these two individuals met when they lived 15 miles apart? Once again, St. Mary’s parish church is a typical small parish church. Inside the church, Mary and I see one of the medieval chests which would have held century after century of parish records. Fascinating.

Set higher than the immediate surrounding land, the parish cemetery has a haunting feel to it. Maybe the fact that so many of the tombstones had sunk into the ground and tilted at strange angles created that feeling!

Who can’t be intrigued by tracing, even in a general manner, ancestors’ geographic locations? Imagining the fields they plowed. The parish services they attended. The known people whose names are inscribed on tombstones. Maybe, just maybe, in some future, I’ll learn more about all of them.