She hears all sorts of words like these. One fellow enters her shop and, we can hear his disdainful description, “a little dirty shop, with hundreds of specimens piled all around.” She writes to a friend “the world has been unkind to me” and “the world has sucked my brains from me.” Ouch!

Look at the statue that has been only recently completed. Initiated by a 12-year old girl who insisted that her community, her world, should recognize this woman. A good likeness if I don’t say so myself. Moving forward with assurance. Determination in her face. Eyes looking down the coast, or is it even further into time? Holding her small, hand chisel as the tool to chisel away misunderstandings about our earth’s past.

Who is “she?” Mary Anning. Who am I? William Buckland. An enthusiast for fossils who purchased fossils from Mary, a student of geology who wrote papers without mentioning her, a benefactor who tried to help alleviate her poverty.

I know the remarkable life and contributions of Mary Anning. A woman who dies in 1847 of breast cancer; a woman who is never appreciated. Or, should I say never appreciated until your day and age when in 2010, 163 years after her death, the Royal Society included Anning in a list of the ten greatest British women who have most influenced the history of science.

A few facts to introduce her. Her father, a cabinet maker, inspires the love of looking for fossils under the cliffs near Lyme Regis. Unfortunately, he dies when Mary was eleven leaving only her brother and mother as her sole family (eight other siblings died in childbirth or in their early years). Due to this working-class status, she and the family continue to sell fossils for income. Poverty never leaves them. Even though she had little schooling, she listens and asks questions of those who purchased her fossils. Eventually, she understands more than the buyers! The dangers of her fossil hunting are obvious. Since the best time to look for unearthed fossils is after a storm, she and her dog Tray would head to the undercliffs as soon as the storm passed. Since the most dangerous time to look for fossils is after a storm, she narrowly escapes death even though her Tray was buried by a landslide.

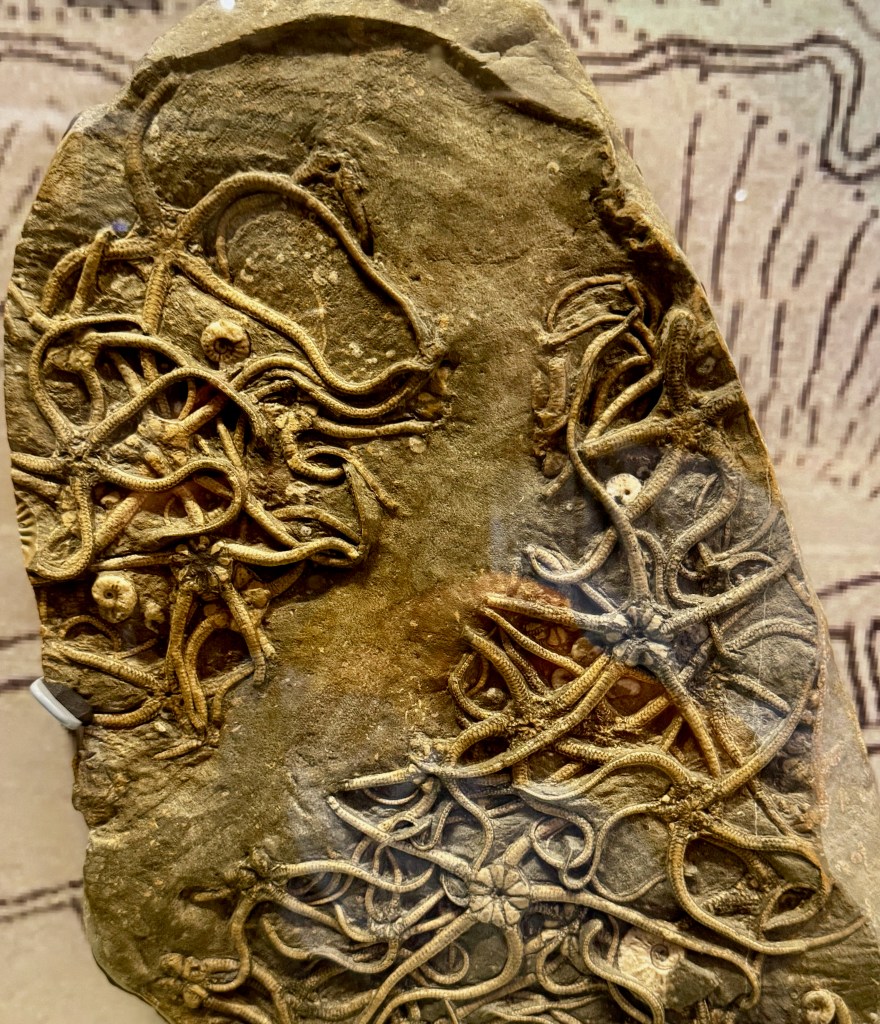

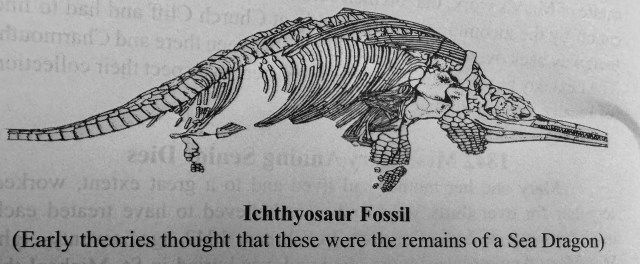

She didn’t find simply pretty colored stones. She found fossils. This particular part of England’s Jurassic Coast has limestone and shale layers approximately 210-195 million years old, an age of dinosaurs and reptiles and amphibians. As some of these creatures died in the shallow sea, their bodies became embedded in sediments, eventually fossilizing.

Her discoveries are amazing. An ichthyosaurus when she was only 12; the first complete plesiosaurus. On and on and on.

I am one of those who was caught by the period’s stereotypes of class and gender. I did not correct my fellow “experts” who ridiculed her working-class status; I did not correct my fellow “experts” who ignored that their own work depended upon a woman’s discoveries. In fact, I can mention repeatedly when the “experts” gave papers at The Royal Academy of Science and Geology and did not even mention that their research depended upon her efforts. One “expert” who did acknowledge that his efforts depended upon somebody else, went on to thank “the man who gave him the evidence upon which his paper was based.”

How does she overcome the belittlement of her as working-class and as a woman? Maybe it is her own fierce pride. Maybe it is that she appreciated the move toward truth, towards “putting the pieces together” by observation, by discovery, by imagining alternative creatures in this created world. Maybe it is her own sense that whatever she learns from her fossil digging and collecting is never a threat to the Big One. Whatever her sense, she continued to work at finding fossils. Perhaps we might say that her vocation was to be a fossil finder, a scientist, no matter what others said or didn’t say!

Of course, many others in the religious world feel threatened. I understand that those threatened folks feel compelled to attack and mischaracterize the very processes of scientific research itself.

Mary remains active in her local parish church. In fact, the church has a stained-glass window dedicated to her. Because of her ongoing faith commitment, I’m convinced that for her our questions about creation don’t center around a particular time of origin, but about a primal, causal, but “non-competitive” relationship between this world and the Big One Upstairs. As one pretty bright English thinker, Austin Farrer by name, wrote: “If it has a gardener, the natural world is a wild garden laid out with so skillful and so self-effacing an informality that the gardener’s hand can never be convincingly detected in any single feature.” Furthermore, this “wild garden” is constantly in movement, constantly changing, with everything from ocean waves to cliffs, from sea gulls to people, active in their own way. While the Big One’s Mind might hold the world together, this “wild garden”, this “world”, is a free-for-all where everything that acts is “being themselves at their own level.” Mary isn’t threatened even by the strangest of creatures in this wild garden, those creatures called ichthyosaurus and plesiosaurus. Nor is she threatened by the immensity of time past during which those creatures must have lived. And, just as Mary isn’t shocked that this Big One almost disguises that there is anyone else besides the wild garden’s elements and creatures, so also Mary isn’t shocked by this Big One’s unending patience beyond time, four and a half billion years of patience.

Despite her poverty, despite others ignoring her scientific work as a woman, Mary feels a wonder at this world. A wonder not despite the Big One Upstairs, but a wonder about this world, this “wild garden”, and its very relationship to the Big One Upstairs.