Everybody in the world knows Gandhi. While our seminar organizers provide a wonderful selection of speakers, one of our most appreciated speakers is Professor K. Swaminathan, the 94-year-old editor of the Collected Works of Gandhi. Upon receiving a master’s degree from Oxford and becoming a professor at Presidency College in Madras (Chennai), he became the Chief Editor of the to-be-completed 90 volumes. Recognizing his immense contribution upon the completion of the last volume in 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi remarked: “I wish to place on record my appreciation and that of the Government of India of the dedication and competence of Professor K. Swaminathan and his team of editors, research scholars and staff who have laboured over the last twenty-five years to complete this monumental work.” Everybody agrees!

He weaves Gandhi’s life and thoughts into his own personal experiences with Gandhi. It is a privilege to listen to his spell-binding stories. As he says, “I’m too old to go to America, so America comes to me.”

Being elderly, Swaminathan doesn’t try to impress us with his most recent, cutting-edge research. Reading from a previously authored article, he says:

“Gandhi tried to spiritualize politics and public life. He made service to the nation a sadhana, a means of attaining moksha.” From Gandhi’s point of view, “the world has enough for everyone’s needs, but not for everyone’s greed.”

Swaminathan prefaces his discussion of certain features of Gandhi’s life by mentioning his own interaction with Gandhi. In 1915, he and other young students met Gandhi. Having lived in South Africa for more than twenty years and returning to India to join the Indian independence movement, Gandhi traveled the country in order to immerse himself in the “real” India. Swaminathan stated: “From the first, meeting Gandhi was like meeting an old friend, not like meeting a stranger.”

Swaminathan recalled some of Gandhi’s words. Once asked to visit a Vishnu Temple in Varanasi, Gandhi replied “Why bother?” When he saw widows outside the temple wearing white (the traditional color mourning in India) with shaved heads, Gandhi exclaimed, “If Hinduism consigns people to such status, then I’m not a Hindu.” Interesting, using many of Swaminathan’s edition of Gandhi’s works in a paper that I wrote several years later, I discovered that Gandhi slowly moved toward a broad criticism of caste. Gandhi remained a Hindu, but he also claimed “India doesn’t belong to the Hindus alone.” Pretty strong language that challenges later political groups!

Gandhi had a sensitive appreciation for all religions. Swaminathan reminded us: “When in jail in 1908 in South Africa, he Gandhi) read the Gita in the morning, the Koran in the afternoon, and the Bible in the evening.” According to Swaminathan, Gandhi saw no difference between the Sermon on the Mount and the Bhagavad-Gita.

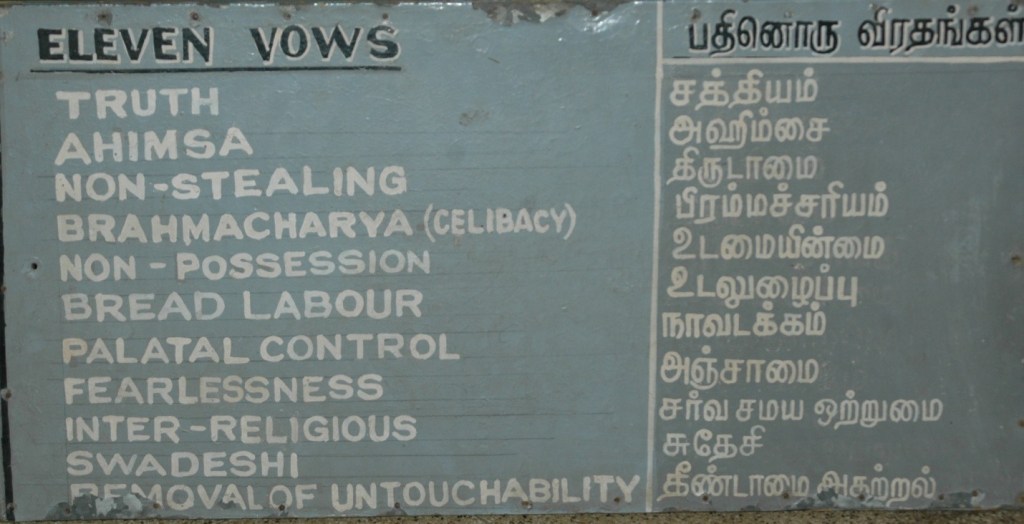

How did Gandhi face the massive suffering he saw? He first had to identify with those who suffered. Gandhi’s early experiences and his education as a lawyer did not motivate him to think about suffering. When he moved to South Africa, he began to identify with fellow Indians as they had migrated there for work. He identified simply by wearing the dhoti. He began to understand the causes of their suffering as primarily due to British imperialism. In the face of this situation and borrowing from the Jain tradition, he advocated for the adoption of ahimsa, a non-violent form of resisting. Also, in the face of massive suffering, Gandhi had another message, become more self-reliant. From food to clothing, Indians needed to reacquaint themselves with basic skills. In the early twentieth-century, that self-reliance required Indians to relearn simple skill as using the spinning wheel and producing one’s own clothes. Eventually, this Gandhian characteristic separated his view from that of his follower and future Prime Minister, J. Nehru who embraced the need for more modern economic practices.

How else did he respond to the massive suffering? Upon returning to Atlanta, my later post-graduate work included reading even more about Gandhi and his responses, especially the American Joan V. Bondurant’s The Conquest of Violence (1958). During his four mass movements, the 1920 Non-Cooperation Movement, the 1930 Civil Disobedience Movement, 1940 the Individual Satyagraha (the word Gandhi used to describe his own type of protest movement), and the 1942 quit India Movement, Gandhi developed and utilized a nuanced campaign of resistance.

Bondurant met Gandhi when she arrived in Delhi in 1944. Her later work the Conquest of Violence became a classic detailing the strategic stages in his satyagraha (“truth force”) campaigns. These stages are: negotiation, preparation, agitation, ultimatum, economic sanctions, non-cooperation, civil disobedience, usurping functions of government, and, then establishing a parallel government. His response to the massive suffering required not only an understanding of its causes, but a creative and nuanced challenge to its reality.

Gandhi was murdered in New Delhi on January 30, 1948 at the age of 78. He was residing as a guest at the home of the Ghanshyam Das Birla, a wealthy industrialist and financial supporter of Gandhi. Murdered not by a Moslem, but by a fanatical fundamentalist Hindu. Gandhi’s cremation occurred along the banks of the Yamuna River in New Delhi, India, on January 31, 1948.

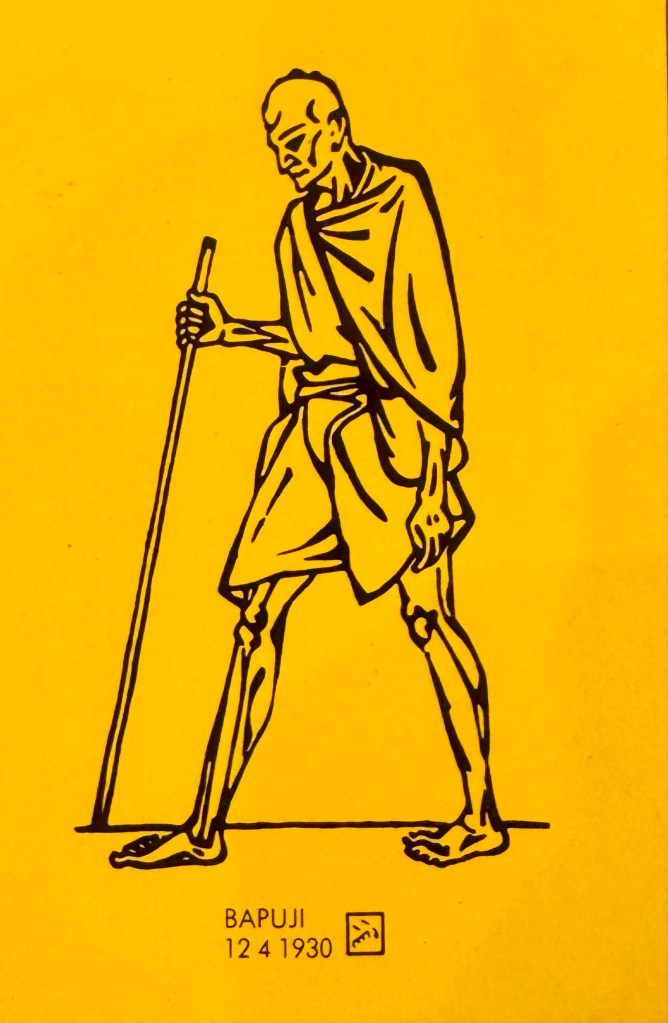

Besides Professor Swaminathan’s words, we saw memorials to Gandhi everywhere. The most striking one is along the Madras waterfront. A statue commenorates Gandhi’s “march to the sea.” While holding non-violent resistance marches in and near Madras, the actual two hundred mile “march to the sea” to fight the English salt tax, took place on the other side of the country. In Madurai, I visit the Gandhi Museum which exhibits Gandhi’s garment worn the day he was murdered.

Since this 1990 seminar, as I have traveled to sites around India and around the world, I’m always struck by the memorials to Gandhi.

Connections can bring a topic alive. Professor Swaminathan brought Gandhi alive to all the seminar participants. What a privilege and memory!