There are many terms for the traditional Hindu social stratification, varna, jati, and caste.

My own seminar goal is to familiarize myself with Hinduism and some of the basic features of religious life in India. Remember: I’m new to studying Hinduism. Obviously, one of the features to understand is the historically influential varna, jati, or caste system. The very words suggest the complexity of India life. The word “caste” originates from the Portuguese/Spanish word casta, meaning “breed, lineage, or race.” The word entered the English lexicon at the beginning of the 1600’s following the Portuguese usage of the 1500’s.While most in the west use the Portuguese originating word “caste,” the other two words are more accurate. Varna refers to the textual and philosophical descriptions of society; jati refers to the actual, social divisions within existing Indian society.

Interestingly, during our seminar, there were no single lecture on varna, jati, or caste; however, it seemed as though every other lecturer touched upon the topic! We could tell that this topic is a bedrock feature of any discussion of Indian society.

Part of the background were two basic realities. On the one hand, while the means of social stratification exists in every society, Article 15 of the Constitution of India prohibits discrimination based on caste and Article 17 declared the practice of untouchability to be illegal. On the other hand, despite being officially banned in 1950 by the Indian Constitution, the system still operates “unofficially.” As several people in India said to me, “Give me two minutes with a person and I can determine their caste.”

We constantly ask questions, sometimes sensitively, other times bluntly. However, here are a few seminar markers in understanding caste.

Professor K.V. Ramen’s “Indian Culture” provided a orienting lecture to the periodization of Indian history. According to Ramen, during this Vedic period 1200BCE-600 BC, the first emergence of a varna system occurred. This classic division was as follows:

The Brahmin are the priests and teachers dedicated to learning and rituals; the Kshatriyas are the political and military leaders who assure protection; the Vaishyas are the merchants; and Shudras are the workers. Connecting these forms of living with religious texts, the Rigveda‘s “Purusha Sukta” hymn describes these castes as originating from different body parts of a cosmic being: Brahmin (the mouth), Kshatriyas (the hands), the Vaishyas (the thighs), the Shudras (the feet). Not surprising that in a religiously saturated society there is a religious legitimation for the order and hierarchy of that society. These “complementary” divisions later, in theory, “became very rigid.”

There are many features of this varna system. Rather than wealth being the determinant of this hierarchical system, the system is based upon purity. According to ancient texts, every Hindu should desire that which will keep him/her pure and avoid that which will stain them. These principles affect every aspect of life, with whom one can eat, what work one might perform, to whom one might marry. By performing one’s duties, a person might be able to be born to a higher level of varna in the next lifetime. There is no change within one’s life to a higher stage.

Besides the systems’ divisions and animating principle of purity/pollution, the system also recognized goals appropriate for the males’ different stages of life. These different goals allowed for flexibility. For example, individuals find themselves in one of four stages of life, ashrama. There are those who are students (brahmacharya), those who have family responsibilities (grihastha), those who are retired (vanaprastha), and then there are those who are renouncers (sannyasins), individuals who will leave family and friends in order to find ultimate liberation. Another example is that individuals can strive for four, very broad goals, the purusartha. These appropriate goals are moral living, economic prosperity, happiness, and ultimate liberation. Whew! Quite a framework both for society and individuals, particularly the males.

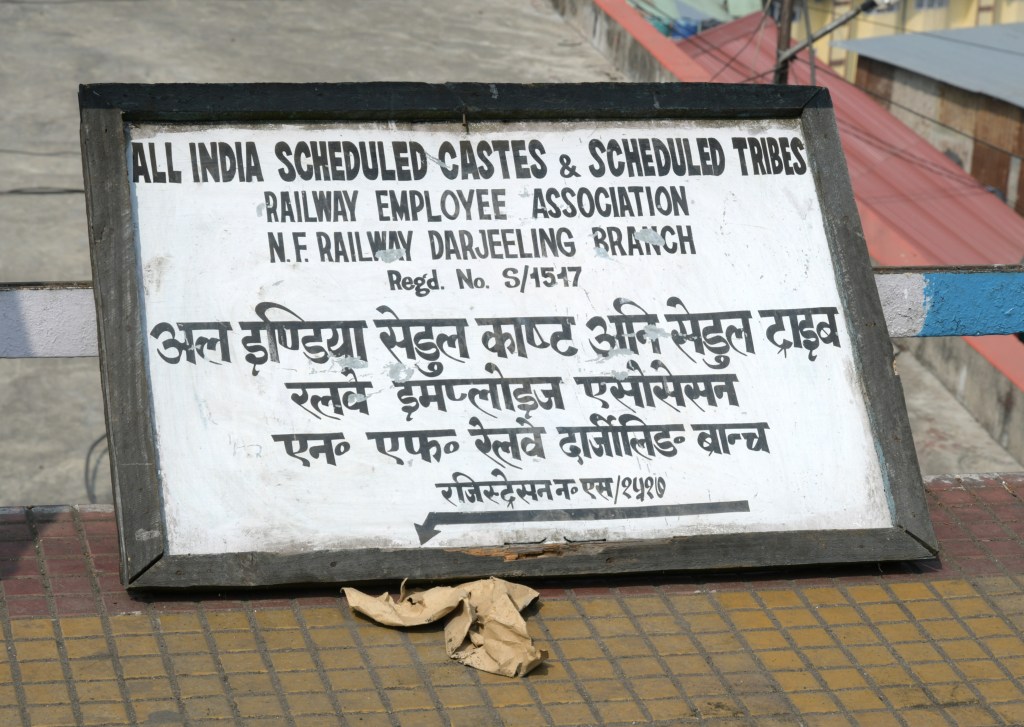

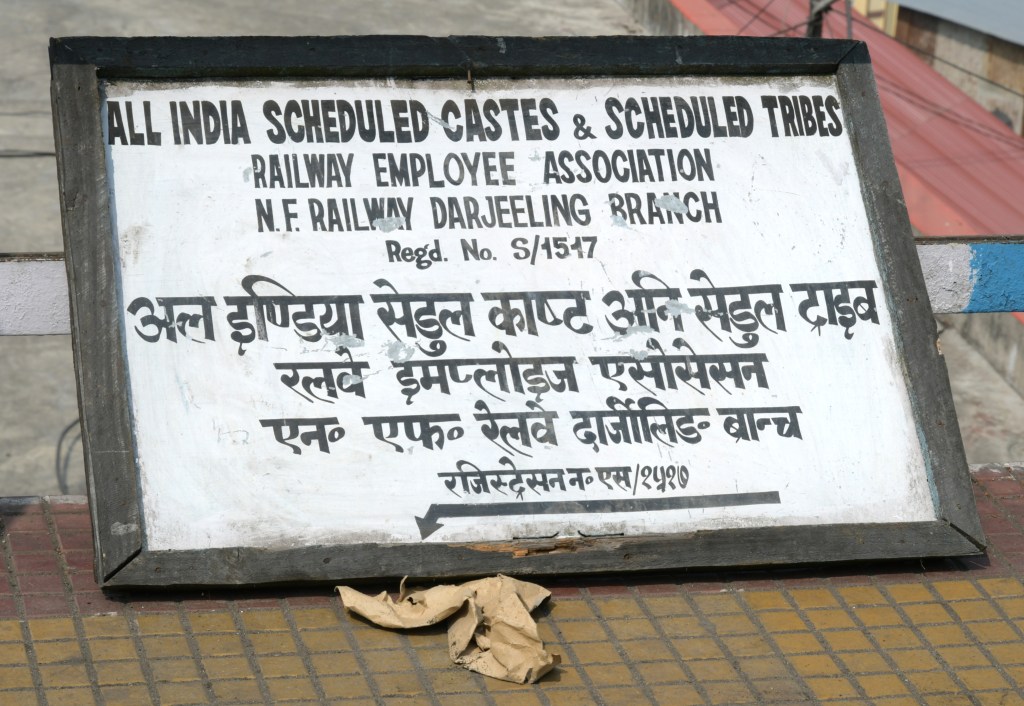

The seminar presenters did not discuss Jati, the actual social stratifications. Reality is always more complicated than the abstractions of thought! Here is my own later input. As it turns out, within these four classic varna divisions, there are hundreds of sub-groups. Although the caste system appears rigidly hierarchical, in reality, there is often no agreement as to the status of these sub-groups within the caste system. Different Brahmin sub-groups fight with other Brahmin sub-groups over whose group is higher in social ranking. Some in India do not even consider the untouchables, or the “scheduled” caste in today’s language, some one or two hundred million people, as even included in the traditional caste system. For those Hindus, the untouchables are outside the caste system. Although the last census which included caste data occurred in 1950, we will soon have a better “guesstimate” as the 2026-2027 Indian census will include such questions about caste.

What was that status of caste relations in 1990? To return to the lectures, Dr. A Gnanam spoke on “The Challenges Facing Higher Education in India.” His historical survey beginning in late 1800’s and early 1900’s involved the slow introduction of Western educational practices. Understandably, college administrators, faculty and students viewed education as a “passport to a job.” Following Independence in 1947, the education system saw changes. One change was the attempt to enhance the primary and secondary education system because the small college enrollments required a feeder system. Within years, 25-30% of state budgets went to this type of education. Another changed affected the “backward people.” In 1955, the First Backward Classes Commission or the Kalelkar Commission was formed trying to fulfill Articles 41, 45 and 46 of the constitution. Realizing a need for greater social justice, advocates began to call for a change that helped “backward people”, the former “untouchables” or Gandhi’s “harijans”, the tribal people (“scheduled tribes”), and other groups disadvantaged and discriminated groups. As a result, states developed a “reservation” system in which certain percentages of admissions were assured and protected for these “backward people.”

Professor Suryanarayan in his “Indian Political Systems” framed displeasure with caste legislation within India’s three theoretical ways of relating the state to an individual’s religious practice. The state guarantees religious freedom; the state treats each person as an individual, irrespective of whether the person is religious or not; finally, the state remains removed, neither promoting or interfering with a person’s religious beliefs and actions. Within this larger theoretical framework, Professor Suryanarayan suggested that traditional Hindu communities have resisted modernization and egalitarianism. Thus, certain Hindu groups have criticized the abolishment of untouchability, the opening of temples to the harijan, and the allowing women inheritance and rights. Jumping to today, certain Hindu groups have continued the criticism of the efforts to undo the damaging effects of society’s stratification.

Varna, jati, caste. The terms describe a reality alive and well in Indian society. As with every society, the issue is how to move toward a sense of social justice given the reality of social differences.