Not only the seminar’s women, but also the men, want to understand women’s roles and status. While we all realize that there is a complexity to this set of issues, we also could not forget ancient texts, older practices, and current exploitation. At its extreme, classical and parts of contemporary India encouraged women’s inequality, subservience, and degradation.

The ancient Manusmirti, the Law Code of Manu, is a collection of writings prescribing the behavior for various castes and individuals as they age. This collection of writings written between 200 BCE and 200 CE makes a dire statement from Chapter IX.

1. I will now propound the eternal laws for a husband and his wife who keep to the path of duty, whether they be united or separated.

2. Day and night woman must be kept in dependence by the males (of) their (families), and, if they attach themselves to sensual enjoyments, they must be kept under one’s control.

3. Her father protects (her) in childhood, her husband protects (her) in youth, and her sons protect (her) in old age; a woman is never fit for independence.

Whoa!!

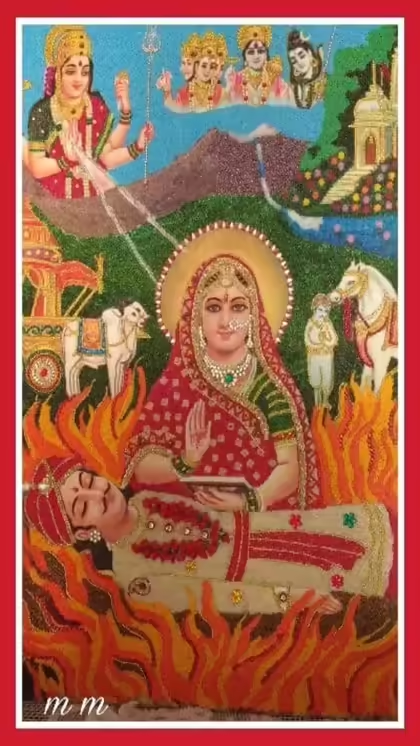

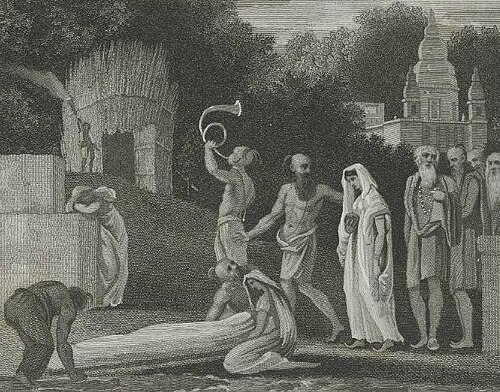

For the seminar participants, the more frightening, and reprehensible practices, involving women was sati. In this practice, a widow would lay down beside her deceased husband on a funeral pyre. When the pyre was lighted, she would be cremated alive.

Upon returning to the States, I read about the compex history of sati. John Hawley edited a collection of scholarly essays in Sati: The Blessing and the Curse. Although scholars can’t determine how frequently it was practiced, the general consensus is that the practice was not wide-spread. Various motives and causes, stated and unstated, triggered this practice. The desire to end one’s life in a “honorary” manner; the difficulty of widows living in a male-dominated society; the desire for surviving family members to acquire the deceased’s wealth.

The history of ending sati is also complicated. At first, the British East-India Society did not want to interfere with Indian social and cultural practices. Thus, they did not remove the practice. Eventually, Hindu reformers such as Ram Mohan Roy and Christian evangelicals such as William Carey increasingly pressured the colonial government to outlaw the practice. Finally, in December 1829 Lord Bentinck issued Regulation XVII declaring sati to be illegal and punishable in criminal courts

William Hodges in his Travels in India described one case of sati. Arriving in 1778 and staying six years, Hodges painted and documented his travels throughout the land. Although difficult to read, his original text is online. In Chapter 5, he describes an occasion of sati. Brief note: the “f” is an “s.”

WHILE I was purfuing my profeflional . labours in Be-

nares, I received information of a ceremony which was to

take place on the banks of the river, and which greatly ex-

cited my curiofity. I had often read and repeatedly heard of

that moil horrid cuilom amongft, perhaps, the moil mild

and gentle of the human race, the Hindoos ; the facrifice of

the wife on the death of the huiband, and that by a means

from which nature feems to fhrink with the utmoft abhor-

rence, by burning.

The perfon whom I faw was of the Bhyfe (merchant) tribe or call ; a clafs of

people we fhould naturally fuppofe exempt from the high and impetuous pride of rank…

Upon my repairing to the fpot, on the banks of the river, where the ceremony was

to take place, I found the body of the man on a bier, and co-

vered with linen, already brought down and laid at the edge of the river…

As at this time I flood clofe to her, fhe obferved

me attentively, and with the colour marked me on the fore-

head. She might be about twenty-four or five years of age,

a time of life when the bloom of beauty has generally fled

the cheek in India…

From the time the woman appeared to the taking

up of the body to convey it into the pile, might occupy a

fpace of half an hour, which was employed in prayer with

the Bramins, in attentions to thofe who flood near her, and.

converfation with her relations. When the body was taken

up fhe followed clofe to it, attended by the chief Bramin ;

and when it was depofited in the pile, fhe bowed to all around

her, and entered without fpeaking. The moment fhe enter-

ed, the door was clofed ; the fire was put to the combuflibles,

which inflantly flamed, and immenfe quantities of dried wood

and other matters were thrown upon it.

Finally, during the seminar’s last days, Carol, Amy, Barbara, and I hire a taxi. Our destination, Bombay’s “Red Light District.” Upon arrival, the four of us stay in the taxi as we drive through the district. The street is busy. Like our taxi, cars are slowly edging their way down the street. Hundreds of men on the street walk faster than the cars! Then there are the women. Women on the sidewalks, on the steps of the buildings, leaning out windows. One of us says to the others “Look how young she is!” “Look she appears to be calling to us!” We are constantly wondering “What kind of life do they have?”

The “Red Light District” certainly seeks women who are desperate. Those with power use intimidation and fear to control the women once they enter the Red Light District. And, of course, the police and government officials, somehow and in some way, are involved.

While I am reluctantly mention the ancient text, the practice of sati, and the Red Light District because I don’t want people to exaggerate their historical or current reality, we begin any discussion with our perceptions. These were our perceptions. We start there, but proceed to the more complicated analysis.

Three other reminders, about the connection of texts to actual life, about the importance of conflicting texts which honored women, and the women who actually fought to improve the roles and status of women. To begin, the Manusmirti text is a part of India’s textual legacy. True of any text thousands of years old, scholars don’t know all the history associated wtih the text, who were the authors, what was their historical context, what are the written or unwritten sources of the text, and more. We also don’t know how the text was received in actual history. Our knowledge is only fragmentary about who it shaped. Following up on that point, while we do know that the text shaped attitudes, scholars can imagine that other people ignored this text and used other texts for guidance. Rani Lakshmibai became a national figure of resistance for her participation in the Indian Rebellion of 1857 against British colonial rule. Indira Gandhi, daughter of India’s first J. Prime Minister Nehru, became India’s first woman prime minister. The multi-faceted history of a textual tradition allows for individuals to accept and reject parts of that tradition, often in ways which lead to contradictory forms of behaving!

Second, as I’ve indicated, we who are outsiders to Indian society and culture should not infer that the practice of sati was practiced universally in Indian society. We should not overlook ways in which people tried to remove sati or to correct abuses of women. We can applaud the reforming efforts of historical figures such as Ram Mohan Roy as well as current women like Ms. Jaya Arunachalam, the founder of the Working Women’s Forum, and Uma and Shuda, our graduate assistant guides, who are pursuing doctoral degrees with the hope of being role models for other younger women.

One final word. We should not overlook our own social failing.We might conclude that women are equal to men in our country and do not face significant social barriers. Ha!