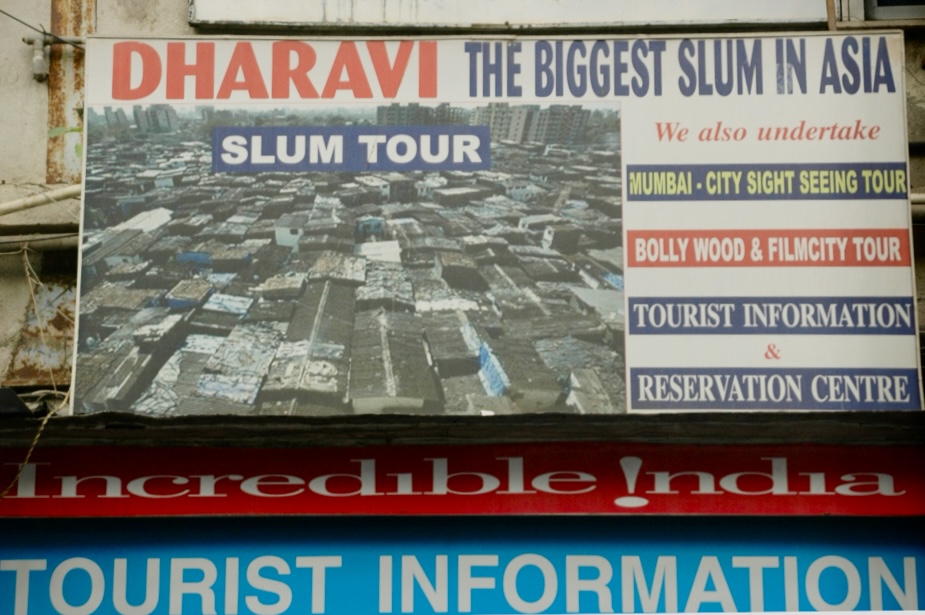

I want to see Mumbai’s Dharavi slum. Reportedly the largest in Asia. Knowing that I’m not going to walk through Dharavi alone, I joined Dava’s walking tour. My last Indian walking tour.

Early that morning, five of us meet Dava. As he introduces himself, we all realize that this will be an interesting guide. Dava was born on a plane! Returning from Dubai to Goa, Dava’s mother delivers him right after the plane lands. Crazy! His step-father doesn’t like him; he favors his own biological son. At an early age, this father says: “You are lazy. You don’t do anything. I’m not giving you any money.” Saying these words, despite Dava delivering newspapers and chai during his primary school years. Eventually, Dava moves out of the household. This twenty-ish year-old young man has only recently become a walking tour guide. He is determined. Living quite a distance north of Mumbai, he rises at 4AM to arrive at the office by 8AM. He usually leads the 8:30 AM and the 2PM tours before he goes to the university for early evening courses completing his Commerce degree. The next day the same routine!

Dava wants to break any slum stereotypes. Knowing that many of us have seen Slumdog Millionaire, he says “Dharavi is more than what you see there. I’ll show you.”

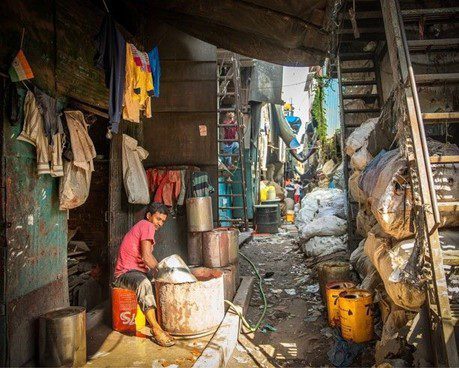

As he led us for two-hour walk through Dharavi, we walk through narrow alleyways. At first, we are to embarrassed to look to intently into the living and work areas that we pass. Yet, as he pauses and chats with people, we feel more comfortable about looking into the areas beyond the alleys. The above internet photo reflects one such alleyway.

Dava carefully describes the slum. There are approximately one million people in an area which is 2/3 the size of New York’s Central Park. While Mumbai has a dense population, Dharavi is incredibly dense.

It is viewed as the “heart of Mumbai.” Mumbai faces the danger of being swallowed by its own filth. Litter everywhere. Debris everywhere. Realizing that trash can be turned into money, the people of Dharavi engage in recycling. From the rest of Mumbai, people bring plastic and aluminum. The plastic is washed, melted, poured into strips, and cut into pellets to be reused. The aluminum is also melted, iron and other metals separated, then poured into molds to be reused. Dava said “The metal work is dangerous. Most workers never survive more than twenty years. Some of them go blind by then.” Mumbai can not exist without Dharavi’s workers.

As we end our tour, I am allowed to take a photo. Besides recycling, Dharavi workers keep busy by laundering! I suspect that my bedsheets and towels might have been cleaned here!

The residents of Dharavi are interesting. Not all the population of Dharavi is permanent. After the harvest season, rural farm workers migrate to Dharavi for several months. Their employers will care for them by providing lodging and even medical help if needed.

In addition to these temporary residents, many Dharavi families have lived there for generations. Dharavi is “home” for thousands. Their residences vary. A 10’x8’ room may cost $20,000! Some of these have electricity, TV’s, refrigerators, and more. Some of these rooms are packed, six or seven individuals might living in that cramped space.

There are plenty of health problems, cholera, malaria, and more. We see a small ¾” drinking water pipe which runs right next to the sanitation ditch. Yikes! People can find health care. There are both government clinics and private clinics.

There are some schools. Education is compulsory from ages 6-14. Government schools are free; however, individuals often make a sad assumption, “something free must be no good.” Of course, this common view can be right when a classroom might be 60 young kids.

After 14, some children attend a private school; however, the price is steep, $60 per month. In addition, some NGO (Non-governmental Organization) schools are free. The reality is that after 14 most children are working. Despite children not receiving additional education, the literacy rate is high, 88% for boys and 74% for girls. The lower rate for girls is usually due to their providing child support for their younger siblings. In addition, if a girl is “educated”, then the girl will want to marry an “educated” boy. The illegal, but unexpected dowry, will be costly.

Dava observes that interreligious relations are tricky. Today, there are usually flags which designate an area as Muslim or an area as Hindu. To lessen possible tension, people eat neither beef nor pork in Dharavi. Before 1992-1933 and the turmoil at Ayodhya where Hindus destroyed a mosque which the Hindus claimed was built on a sacred Hindu spot, Hindu-Muslim relations were not troubling. With that Ayodhya incident, thousands were killed throughout India; 325 were killed in Dharavi. Interestingly, the slum’s riots and killings were calmed down by politicians, even though the same politicians had stirred up the population originally. Why the change of heart? Elections. Before the next elections, the politicians realized that they couldn’t ignore a million voters!

The reported crime late is very low. It helps that 60% of the police force lives in Dharavi.

Dharavi has a sense of community. If a person receives mail, since Dharavi is arranged in blocks, then a person simply places the name and certain block. If a person gets sick, then there are clinics staffed with nurses and doctors. If a person needs employment, then neighbors offer suggestions for how to find work.

Dava exudes a sense of pride for Dharavi. He also breaks some of our stereotypes of a slum such as Dharavi.