Like Delhi and Madras, Kolkata shows its colonial past. Whether walking or using a taxi, any person will see the buildings of the British “Capital of the Raj.” From 1772 until 1911, the city served as the administrative, commercial, and cultural center of the colonial India. Some even referred to it as the “Second City” of the British empire. As Ritwick leads me through central Kolkata, I’m struck by the colonial British architecture; I recall an unforgettable 1990 experience; and as we visit St. John’s Church, we hear a different narrative of Kolkata’s “Black Hole.”

As Capital of the Raj, I’m struck by the architectural reminders of that period. There is the large, red brick High Court with its central tower built in 1862, the older Writers Building built initially for the East India Company clerks in 1777.

Without a doubt, the most impressive building is Queen Victoria’s Memorial. Following Queen Victoria’s death in 1901, this white, marble building built between 1906 and 1921 seeks to honor her memory.

I can’t help to think how improved the memorial is now. When I visited in 1990, the exterior marble had turned yellow from urban pollution; there was evidence of rain water in the interior; and rare and expensive paintings exposed to people’s fingering. I know that if I noticed these conditions, then there were probably other unseen conditions degrading the memorial.

When I approach the memorial today, I see a beautiful white marble building surrounded by beautiful landscaping. On the interior, I visited several halls with both artwork and interesting exhibits. Even though I suspect Kolkata budgets are tight, the government seems to have spent money well to restore and renovate the memorial.

A vivid memory from 1990 plays in my head as I walk past British colonial era buildings. In a small, dark room, Subodh took Carl and me to meet and hear the story of 87-year-old, Ms. Webster. In the 1800’s, her grandfather served in a British military unit station at Madras; her father remained and worked in India for the Eastern Telegraph Company. Living in Kolkata most of her life, she served Thoburn Methodist Church as the church secretary. It was her family.

When the three of us visited her that afternoon, she lay on a small bed in a one-room apartment. Covered by a white sheet that June afternoon, I remember her weak voice, her sallow complexion, and numerous bruises on her forearms. Although she was cared for by a neighboring Muslim family, she had outlived her siblings and her friends.

Looking at her, I saw an aging witness to western presence in Kolkata. One vibrant, now approaching death.

Since Ritwick knows that I teach religious studies, we visit several churches, St. Paul, St. Andrew, and St. John. At St. Andrew, Ritwick tells a humorous story of “pastoral envy.” In the 1800’s, the pastor of St. John’s church wanted his church to be the tallest in Kolkata. The pastor of St. Andrews was shrewder. Not only did he construct a taller steeple, he placed a rooster on the top of the steeple. Why? “So he could crow over the St. John pastor!” Did Ritwick the guide take some liberties with a story? I’ll never know!

Concerning St. John’s church, while the Armenian church is older, this structure still dates back to 1787. Modeled after London’s St. Martin-in-the Fields, the church served as the cathedral for the Church of England until the newly built St. Paul’s became the cathedral.

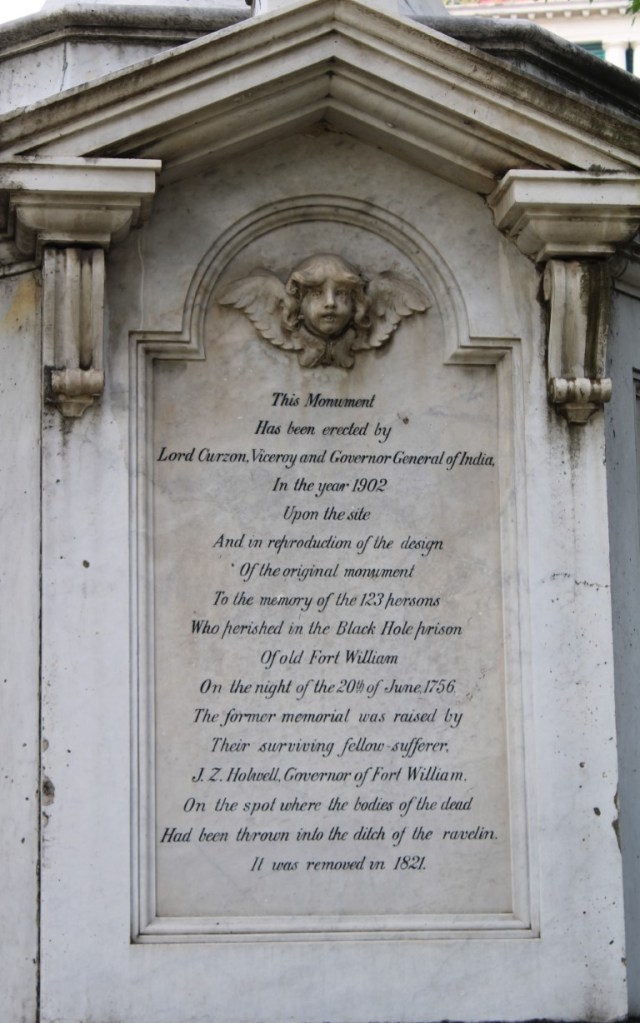

In the church’s cemetery, there is the Holwell Monument, or the “Black Hole” memorial. The backstory is that the local Bengali ruler got angry at the English traders for fortifying their Calcutta “fort” or “factory.” The ruler attacked and captured the fort on June 20, 1756. As the surviving English and numerous Indian sepoys were gathered in front of him, John Holwell, a East India Company employee and the temporary governor of the fort, complained about his hands bound in chains. The ruler ordered that Holwell’s hands be untied; the ruler also guaranteed that nobody would be harmed. The ruler left and authorized one of his commanders to remain in charge of the fort and prisoners. Unfortunately, the situation changed by later in the day, possibly due to an English trader harming a guard. As a result, the prisoners were herded into the fort’s “prison”, a cell 18 ft by 14 ft with only one window. By the next morning, 40 individuals had suffocated from the heat.

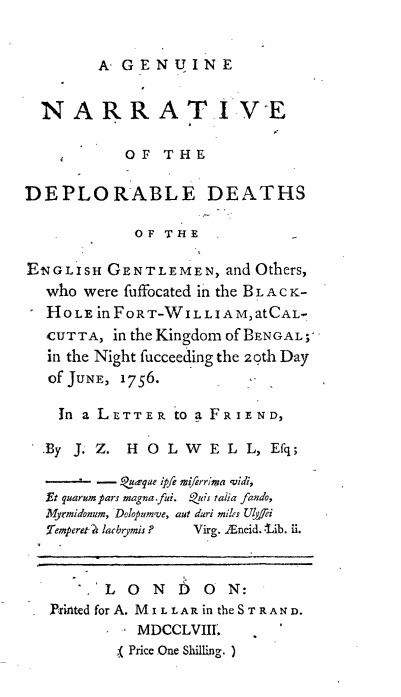

That isn’t the narrative that reached England and that dominated the remembered event. Back to the cemetery memorial. News spread quickly to the British at Madras. In his 63-page book published in 1758, Holwell claimed that 123 of 146 prisoners.

The narrative had immediate effects. The narrative became the precipitating cause for war the next year. In Madras, Lord Clive collected British forces for the East India Company, secured allies with other Bengali forces, and defeated the Bengali ruler at the Battle of Plassey the next year. The narrative became the justification for viewing the Indians as barbaric, for legitimizing the military actions in India, and, subsequently, for turning India economically into the “jewel in the crown.”

In essence, yes, there were deaths in Kolkata. Yes, individuals did die in the prison cell. However, Holwell offered a distorted narrative about the event. In his exaggerated narrative, the English found justification for taking over India, for almost 200 years.

As I write this blog, I read and see news about a city 7,000 miles from Kolkata, Minneapolis. I’m dismayed by the recent narratives about the killing of Renee Good and Alex Pretti.

“Domestic terrorists” by Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem. Pretti was ““brandishing” a gun” by Noem. Pretti was “An assassin…who tried to murder federal agents” by White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller. “Pretti “wanted to do maximum damage and massacre law enforcement” by Border Patrol commander Gregory Bovino. Others picked up on their narrative. On Fox News, Patel (FBI Director Kash Patel) responded to a question about the killing of Pretti, “You do not get to attack law enforcement officials in this country without any repercussions.”

No matter how widespread, distorting narratives have consequences. We are seeing once again, the dangerous consequences of false narratives.