One of my goals is to extend the range of my understanding India’s religious diversity, both within major religious communities as well as between religious communities. Becoming familiar with Bede Griffiths and his Christian ashram accomplishes one of these goals.

Spending a full day and night at the Saccidananda Ashram allowed me to talk with Father George, with several monks and other visitors, and to read about Griffiths. Alan Richard Griffiths lived from December 17, 1906 until May 13, 1993. While his fame developed because of his participation in the Christian Ashram Movement, his earlier life did suggest an unusual life. Born in England, raised in the Church of England, he attended Oxford where he became a life-long friend of C.S.Lewis. After graduating from Oxford, Griffiths and two other friends moved to the Cotswolds and began an “”experiment in common living.” They supported themselves through farm work and reading the Bible together.

Although the “experiment” lasted only a year, Griffiths decided to seek ordination in the Church of England. Asked to work in London’s slums, the work brought on a crisis. After residing at a Benedictine monastery, Griffiths converted to Roman Catholicism. As a Benedictine novitiate, he was given the name “Bede.” He became a Roman Catholic priest in 1940.

His meeting an Indian Roman Catholic priest intensified his interest in Indian religious literature. The priest encouraged him to start a monastery in India. Reluctant at first, Griffith’s superiors finally gave him permission. In 1955, along with the other priest, he moved to the southern India. Griffiths wrote “”I am going to discover the other half of my soul.”

From 1955-1968, Griffiths and a Belgian priest had an ashram in Kerala. When the Saccidananda Ashram in Tamil Nadu faced a turning point because of the death one ashram’s founders and the other’s desire to live as a hermit, Griffiths and two other priests were asked to lead the ashram.

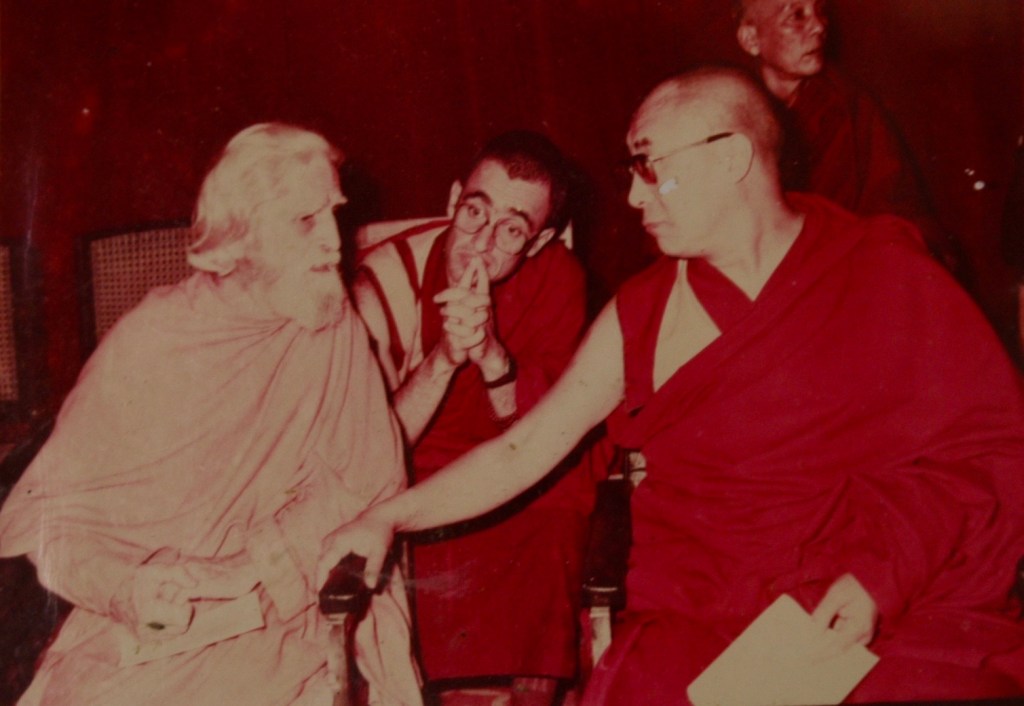

He stayed at the ashram until he died in 1986. Writing. Giving talks in Europe and the United States. Conversing with other spiritual leaders. Quite a journey!

Griffiths wanted to “bring into the Christian life the riches of Indian spirituality, to share in the profound presence of God.” Despite considerable resistance, Griffith’s work resonated with the documents of Vatican II, especially the documents on “Other Religions.” Members of the Indian Council of Roman Catholic Bishops wrote about the “beauty of Indian spirituality.”

I talk with Father George about some of the basic ashram practices. When Griffiths came to the ashram, he found that the original founders had already incorporated aspects of Hinduism into their daily life. Griffiths continued and expanded this tradition. He wore a saffron robe; he vowed to be vegetarian; he sat on the floor to eat; he ate with his hands; and he embraced poverty. All of these are traits of a Hindu sadhu. Furthermore, each ashram monk lived in an individual thatch hut, but they gathered together in common worship. The communal gathering and the individual quarters allowed a combination of prayer and meditation.

When I join others for the common worship in the round worship center there are probably twenty people. We gather in silence. Facing the front in a semi-circle, ten or so who are more flexible sit on cushions in the middle; another ten of us, also facing the front, sit on seats along the outer walls.

With the ringing of a bell, the service begins with the slow chanting of OM. We join together in responsive prayer, a reading from the Psalms, a reading from the Upanishads, and then the Lord’s Prayer. Rather than spoken words in a homily, these words of prayer and Holy Scriptures, we sit in silence.

Father George explains that worship also combines features of both Christianity and Hinduism. In the ashram’s rural setting, they especially value worship at sunrise and sunset. When the service begins with the verbalizing of OM, understood as the primordial sound of creation, Father George likens the sound to the Christian words of John 1 “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God.” In addition, while not occurring during the service I attend, there is also the practice of Aarti, the gentle, circular moving of a lit candle in front of a person and that person placing their hands over the candle. Such an act symbolizes welcoming the other person and holding that other person in respect and love. So many ways in which Griffiths and the ashram join Christian practices and Hindu practices.

I thoroughly enjoy my day at the ashram. This form of Christian community certainly challenges the exclusionary views of so many Christians. “Be like us or you go to Hell.” “Accept my version of the Christian faith. It is the only true version.” Griffiths challenges those attitudes as he experimented with his life, as he journeyed all the way to India to find the presence of God already there.

For one who loves to travel and take slow-walks, I love the quote: “Theology is like a map. Merely possessing it does not make us travelers; we must take the journey ourselves.”