While I enjoy wandering around a place by myself, I know that there are times a guide is indispensable. In Dharamsala, Dholdun is my guide. Born in China’s Autonomous Region, he has lived in Dharamsala since his fleeing China in 2005. Although only a guide for three months, he is eager to show and teach me about the Tibetan communities in India.

Dholdun reminded me of the basic story concerning the Dalai Lama and upper Dharamsala (or McLeod Ganj). Beginning with the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950, the Chinese increasingly dominated Tibet. Due to the killing of thousands of Tibetans and the destruction of its culture, the Dalai Lama and a small group of followers fled Tibet crossing over the high Himalaya passes in 1959. Fortunately, Prime Minister Nehru granted he and the other Tibetans asylum and land in upper Dharamsala.

Since then, Dharamsala has the imprint of Tibetan Buddhism. On this mountain ridge, there are buildings built on top of each other. Here, and in nearby areas, the Tibetan presence is vividly marked.

The focal point of the Dalai Lama’s presence is in “Little Lhasa.” The Tsuglagkhang Complex includes his residence, the Namgyal Monastery, and the Tibetan Museum. Although on my first visit there are no monks present, Tibetan laity are circumambulating the temple or the larger exterior wall with its prayer wheels. Occasionally, I see several men fully prostrate themselves as they move around the temple; usually, I hear and see most of the Tibetans quietly chanting and handling their rosary beads as they move clockwise.

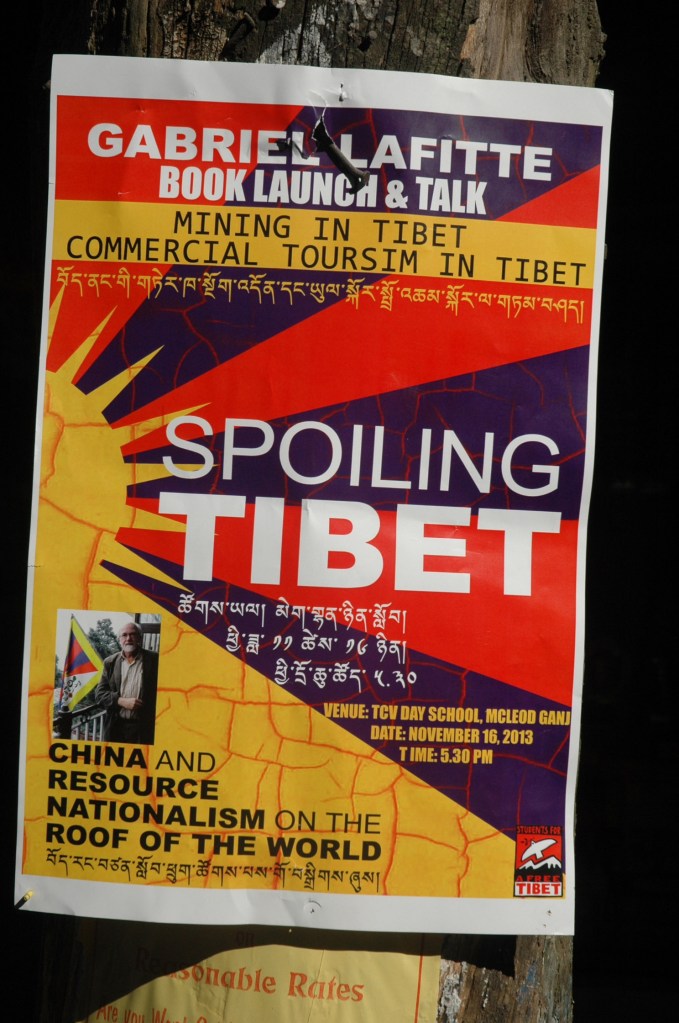

Nearby is the Tibetan Museum and the Gu Chu Sun organization which monitors political activity in Tibet, especially the life of political prisoners. Similar to looking at victims of the Holocaust or other figures of torture, I can’t help but wince and quickly look away from some of the tortured Tibetan political figures photos.

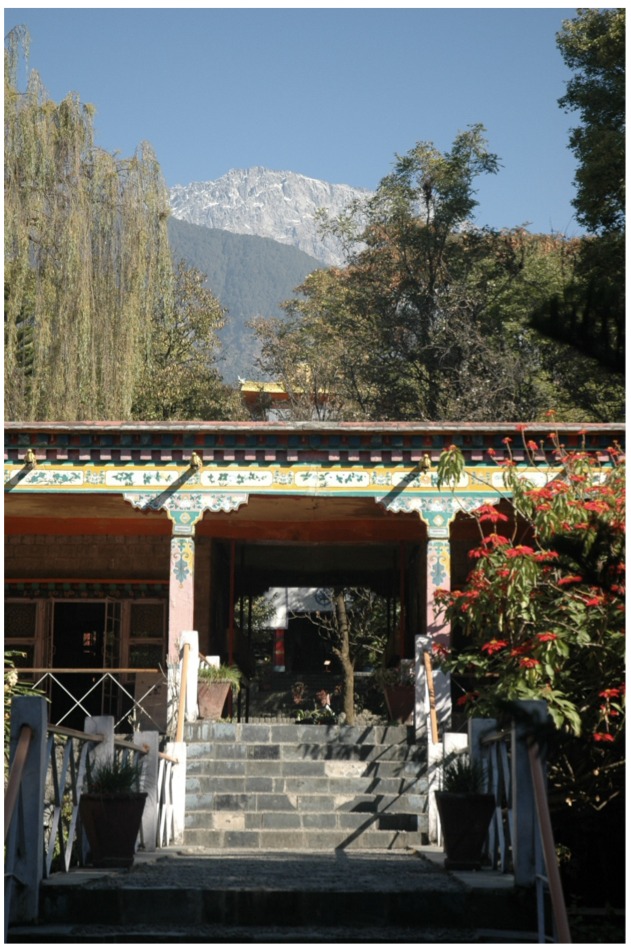

Dholdun wants me to become aware of other features of Tibetan Buddhism. Not far, but outside of Dharamsala, are the Norbulingka Institute and the Gyuto Monastery. Established by the Dalai Lama, the Norblungka Institute is an attempt to keep Tibetan culture alive. The Institute is set in a beautiful setting, the mountains in the background, prayer flags fluttering, evergreen trees providing shade. Approximately 300-400 Tibetan artists are being trained wood carving and painting, thangka painting, and metal working.

We also visit the Gyuto Monastery. Within the broader Gelug tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, there are other important traditions. Tracing its history to the 1400’s, approximately 60 monks of the Kadam school of tantric Tibetan Buddhism, also fled Tibet in 1959. With the assistance of the Dalai Lama, they were eventually able to build the Gyuto Monastery.

As Dholdun and I visit the monastery, we are fortunate to hear two monks blowing horns to gather the monks for chanting and sutra reading. Several young novice monks move quickly along the six lines of monks, probably one hundred monks, filling tea bowls.

We end our day visiting the Tibetan Government in Exile. Funded by private donations, his organization seeks to help Tibetan peoples. After the 71-year old Dalai Lama renounced his permanent political and administrative authority in 2011, the Tibetan Government in Exile officially became led by the Sikyong. Every five years, all Tibetan citizens are entitled to participate in the election. How times change!

Having visited Tibet in 2005, I had my eyes open to Tibetan history. Dholdon helped revive both those memories of the harsh Chinese treatment of Tibetans and the courageous Tibetan effort to preserve their culture.